“The Butchering Art” Reveals the Macabre Legend of Joseph Lister

-By Michael Pierce

While not a book for the squeamish, those interested in the more macabre history of medical research should look at Lindsey Fitzharris’s book The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine, published by the Scientific American/Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2017.

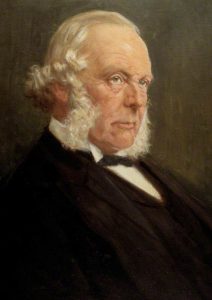

Lindsey Fitzharris has written an excellent book detailing the early life and a large part of the career of Joseph Lister, the early proponent of the scientific method of medical research and the father of the use of antiseptic surgical practice.

Lister had the good fortune of being into an inquisitive, inventive family. His father, Joseph Jackson Lister, perfected the microscope, and his microscopes are still considered to be some of the best ever manufactured.

Joseph Lister exhibited an early interest in surgery, learning the art eventually from world renowned surgeon James Syme at the University of Edinburgh. It was during his time there that he began his serious study of the cause of various types of sepsis that, at times, would kill up to 50 percent of surgical patients.

Joseph eventually began a correspondence and deep friendship with Louis Pasteur, who was beginning his research into what would come to be known as germ theory. Lister was an early proponent of the use of antiseptics in the operating room, specifically carbolic acid.

There was just one problem. Carbolic acid powder was usually mixed with water. As the water evaporated, only the powder was left behind, and this quickly became an issue as up to one third of Lister’s patients still died of infection. Using water for the mixture was fine for the surgeon to use to wash his hands and instruments, and to irrigate a wound before the wound was closed. What Lister need was something that would form a paste that could be applied to the wound after suturing was finished.

Lister hit upon the idea of combining the powder with olive oil. He soon discovered that this combination formed a paste that could be applied after the surgical wound was closed, left for days or weeks at a time, and removed. When removed the stitched area was healthy and nearly healed.

Lister had a difficult time convincing his associates in Great Britain and America of his success, often referred to as quackery by his fellow surgeons. His greatest advocates were his students, a couple of well-placed associates, and Queen Victoria. He received her imprimatur after removing an abscess from her armpit using his antiseptic method, and it wasn’t long before his classes in surgery were overflowing.

Lindsey Fitzharris places readers in the operating room with Lister and his contemporaries, and all the accompanying sounds, smells and gore that were omnipresent in medical facilities of the middle and late 19th century. Reading this book, I actually felt empathy not just for Lister and his struggles, but also for the patients who fell under his knife and the knives of other surgeons, especially before the adoption of chloroform as an anesthetic in the 1840s.

Fitzharris also has the advantage of having been able to conduct her research at some of the world’s great medical archives, and she puts her skills as a medical historian to good use. Posterity also owes a huge debt to Lister’s nephew. Lister died in 1912, and his will stipulated that his personal papers were to be destroyed upon his death. It was the one part of the will that the nephew ignored. It’s those papers that brings Lister to life in the book, informing readers of his frustrations with some of colleagues and his own moments of self-doubt, when he sometimes wondered if his efforts were worthwhile.

Thankfully, they were.